- Home

- Camille Roy

Honey Mine Page 11

Honey Mine Read online

Page 11

Putting your secrets into someone who is lower class is an odd form of hoarding. It’s a bit like stuffing a person as though she were a piggy bank, except that this kind of piggy bank might waddle away. I’d like to think that’s one of the things this essay is doing: waddling away with those secrets. But a friend pointed out to me that secrets aren’t really told unless they’re told to another ruling class person. After all, the servants know everything and no one cares.

7. Poem Interlude

Girlish cloud condensed along wire

With two ghost feet

And a brain of

Feathers. All nerve and

Wanting the real the

Impossible.

My whiskered genitalia. My future as a slut.

With these I went crawling through the whole

crabby army.

8. A Lady of Fashion

I’m not built like the women in my father’s family. They are thin enough to seem wind-whipped. Tough but delicate, like whippets. I do have his eyes, a family characteristic so marked it’s a little creepy. Not just the color (we share precisely the same shade of yellowish green) but the thin arched brow which thickens and sinks slowly with age. We had lunch one day and regarded one another over bowls of minestrone. He had my eye, but bigger, I thought. I couldn’t differentiate myself in the river of his ironic gaze.

If thine eye offend thee pluck it out. Then, buster, hand it over. Theft and gift indistinguishable. In that tangle is the reason Ethel called up one day and told Thomas and Pearl she wanted me for a weekend. She was going to teach me how to select, and shop for, “an outfit.” I had been in college for about a month, and while I hadn’t come out as a dyke yet, I was beginning to gear up for that. Nonetheless, I got a princess rush off the idea (wouldn’t you?). Plus there was the festive prospect of free clothes.

My first mistake was to arrive a little late. Two-and-onehalf-hours late, in fact. I cannot remember why this happened, or how I justified not calling her. It got our weekend together off to a rocky start. From the moment she walked up to me in the train station, I learned about breathing deeply and exhaling calming phrases… Oh Grandmother, I am so sorry.

That evening, we began going through the motions of an education in selecting fashionable attire. Sitting next to Ethel on one of her spotless white couches, I was a rapt student as she did some compare and contrast with the French, Italian, and British editions of Vogue. The following day, we did a grand tour of the department stores, and I ended up deep inside some luscious wools, feeling lost, in fact. I recall the sleeves of the plush mohair wrap had to be artfully rolled up, or they hung down around my knees. The skirt was tight around the waist, but so generous down below I felt like a lady emerging from a lake. Tottering with Ethel through the racks, I ran into only one person I knew, and it was my best friend. We stared at one another in shock. Later that evening, I got to wear my new clothes out to dinner with a retired ballerina.

But the apologies never stopped. It was the weekend of apologies without end. I began to identify with Little Red Riding Hood, in her failure to placate her wolfish grandmother. After returning from dinner with the ballerina, Ethel fretfully catalogued all the insults I was guilty of over the years. A long list, I’m afraid.

With each new item, I tried again to soothe the wounded Ethel, but nothing I did could stop this grief and paranoia from escalating. I don’t recall everything on the list. I do remember Ethel frantically gesturing at a place on her white living room carpet, telling me that at the age of five, Camille (thinking no one was looking) had dropped her cheddar cheese puff precisely there, and ground it in with her heel. But Ethel had spotted it, and had lived with the stain (which I couldn’t see) ever since. The climactic accusation occurred in the dining room. Ethel turned with a ferocious suddenness and described an incident years before at the Thanksgiving table. Ethel customarily served roast beef. All was well, until the wild Camille began spearing pieces of roast beef and carrying them to her mouth with her knife. This brought sighs of horror, as everyone turned to stare, transfixed by the image and possibility of blood gushing from Camille’s mouth all over the holiday table.

Uh-oh. I was out of my depth. My melody of apologies trilled on and on. I left her apartment the next day as one flees a prison. I had worked hard for my clothes, it turned out, and I never wore them again.

9. I, Claudia

I want to wrap this up, I really do. It’s like what parents say before they spank their children—Trust me, this is harder on me than it is on you (although you were right to suspect the parents of having more fun).

What was the matter with Ethel, anyway? Her own mother, of course, Claudia. She hated Ethel. I have a portrait of Claudia, a delicate turn-of-the-century pastel of ungodly size. When I was very small, Pearl told me that I looked like that lady in the picture, with the peacock feather and pearls and elaborate hair. The cooler perspective of adulthood brought the realization that there is no resemblance at all, but the attachment had been formed. Now Claudia is with me. I snatched her from her spot in the dining room during that posthumous tour of Ethel’s apartment, then had her shipped. She arrived in a crate so big, opening it was like breaking into a coffin (which was a lovely moment, if a little spooky). I leaned her against the wall in my shabby Victorian apartment, which had rotten window sills but a marble fireplace and a chandelier dropping flecks of gold paint. Perfect.

Claudia was a big slut, despite her long marriage. Between the wars, she particularly liked prime ministers of deteriorating European republics. In the portrait, her expression is grim, reserved, a little disdainful, but photos show her with a devilish smile. Cruel but sexy. She did the most romantic damage when she was in her fifties and quite stout, wading through society in her embroidered velvets and ridiculous hats. As for what she did to Ethel, only one story came down to me. She made Ethel receive her gentlemen callers in the ballroom in the winter, which was unheated. That puts the temperature at about twelve degrees fahrenheit.

When I was a kid, I’d heard rumors of Claudia writing something. A sort of diary, mixing her escapades with various literary and political musings. I wanted to get my hands on this diary (wouldn’t you?), and after some surreptitious searches, I eventually found it, all ten pages. What remains of it in my memory is her jocular attitude, which struck me as arrogant and overly familiar, and her observations on class in the United States, as compared to class in Europe. These boiled down to—it matters over there, isn’t that yucky, but it doesn’t matter here. Aren’t we lucky?

10. Striptease

After I moved, I put her away. There was just no room on the wall for her big self. Claudia is now in my closet, growing mildew on her eyelashes. She died long ago, and I never even met her. An easy subject. Why didn’t I stick to her? Why, in other words, this orgy of trashing the living?

Hmmh…but I’ve hardly begun! I…rather, Camille, could go on like this indefinitely. For this house of incongruity has many rooms, and each has a place for my shadowy presence, but also has no place. The result being that I’m unnerved by my own disappearing acts and startling reappearances. What is American class? What elements compose a class-based identity, and what happens when those elements are mixed?

I detail the experience without making it intelligible. The class codes become visible, but that’s hardly comforting. There’s nothing homey about a set of rules. They were there before I inadvertently broke them, and they’re still there.

One observation emerges from this which seems worth pointing out. Silence is one way of negotiating the unacceptable. Transgressive romantic fantasy is another. They’re tools for managing the survival of self—the first maintaining it, the second an act of invention. But you can’t separate the tools from their context, in personal necessity, social power, and class.

I’m re

minded of a story Lydia told, about Pearl—yet bear in mind, Lydia was not the soul of reliability herself, especially when the subject related to slippery Pearl. She was too tempted by comeuppance.

Lydia was visiting Pearl. Older sister Pearl was escorting younger sister Lydia about town. Younger sister was somewhat intimidated by the witty communist mathematicians who comprised older sister’s ‘set,’ but, being plucky, along she went, here and there, including, late in the evening, a foray to a strip joint. (This was in the late forties.) Something happened in that bar which Lydia never forgot. They had microphones wired in unpredictable places. After Lydia discreetly disappeared in the direction of the ladies room, Pearl told the bartender to turn the toilet mike on, and the club was doused, so to speak, with the sound of Lydia pissing.

It seems to me that the writer’s role has similarities to the role of that microphone. Given the alternatives of silence or fantasy, ruthlessness becomes the middle way, inescapable, if not always truthful. What do you think? Where would you draw the line… What part of your life belongs to you, and what part belongs to me, should I happen to find out about it? Would it be different if that weren’t Lydia pissing, but just a tape—a simulacrum of Lydia pissing?

I used to believe the key to getting to the heart of the matter was a willingness to be ruthless—an impulse that doesn’t move me quite as much anymore. Where has it gotten me? I am the only one in my generation who knows there had been a murder in the family. Over the years, my father and aunt discussed it around me. They thought it was likely my great-uncle Jack, a hapless man who only had a job because of my grandfather, had also been a victim. Because of timing, and the fact she used poison, this could never be substantiated. She was nailed for the murder of her son. He hadn’t been a baby at all. She poisoned Michael when he was eighteen because she didn’t want him going away to college.

Lately I’ve been thinking that I am a wave, and all the stories in the world are the water. I’m among stories, just like all the other waves. Which part of the water belongs to which wave doesn’t actually matter. It doesn’t apply. Personally, this means I can’t fall apart without changing into something else, other stories, different ones. This finds a solution in dissolution. Somehow it relaxes me.

I am waiting in line for a movie at the Castro when I see them in front of the ticket booth. They are leaning towards one another; there is an atmosphere of indecision. The tall one, the one I love, looks just like she does in the ads. She’s even wearing the same outfit. Thick wavy hair, soft toothsome leather jacket, spotted leopard pants. Big heels. Her date motions with a hand and runs off using short steps. This signals a short absence. The woman in leopard print stretch pants walks over to me. Her name is Lynette; we’ve been introduced. She has a wide mouth and wide eyes; large brown irises. She hands me a folded piece of paper. ‘A party,’ she says. ‘I hope you can make it.’ ‘This weekend?’ She nods, I nod. I put the paper in the pocket of my jeans jacket. She walks back to wait for her date. She puts all her attention into that. I take this as a sign that she’s at work.

I bring a friend to the party. I am feeling insecure and my friend has a low, husky laugh. She isn’t moved by much. Small and hard like a hazelnut with lovely facial bones. Many people are attracted by her aura of experience.

I recognize some of the women at the party as strippers I’ve seen at the Baybrick’s show. Wrapped up in red or black lace, they are noisy and demonstrative. It’s a screen I can’t penetrate. I am vaguely uneasy with the amount and variety of drugs being consumed. My friend and I wander through the crowd with cigarettes and glasses of gin.

Sometimes I see Lynette. She’s wearing big dark clothes, kind of sloppy looking. I assume this means she’s not working. Clothes are conductors in the electrical sense. I want to slip my hand under her shirt.

I am happy when she looks at me. Some sort of recognition, then waiting.

Sitting on the carpet eating a carrot stick. Lynette walks over, quickly nudges me hard under the throat. I lean back on my elbows, her hand slides over my shoulder, presses me down. I feel very hot, I think this is what I want except I also want to finish my carrot stick. She is sucking my neck, which has become soft and elastic.

In my mind I say, ‘I am the beloved of the whore with a heart of gold.’

‘But I don’t love you,’ she says.

‘You’re some other whore,’ I say.

I’m only doing this because my beloved is unavailable.

She comes back from the conference with Lucy, a woman I am jealous of. They are agreeing that the conference was peculiar: paying eight dollars to hear one male psychiatrist present his handling of a case while two others attack him in minute detail. I am curious whether the psychiatrists, by attacking one another, can come to be on the side of the client, who is female. Then, if one changes his position, does his relationship to the client also change, or is this fixed…

I’m not in the habit of revealing my thoughts. Privacy is a service I perform; it’s arbitrary what I reveal and what I don’t. I say, ‘Silence is drainage.’

One of the most interesting ways of making narratives within narratives complex in gay porn is the use of films within films. Many gay films are about making gay porn films; and many others involve someone showing gay porn films to himself or someone else (with the film-within-the-film becoming for awhile the film we are watching).

(Richard Dyer)

Interrupted. My erratic motion toward the ‘sexual fringe’ means the characters fall off before we get to see them fuck. Anne flicks her wrist when she says, ‘I can’t understand why my friends don’t invite me to see them fisting.’

Anti-porn, where the narrative is taken out.

My tongue is a fish wife, flowing and stuck.

Messages sliding over glove-like intrusion.

I decide my beloved ought to be more jealous of me than she is. First, I get my waist cincher, which has an amusing way of making me sit up straight, and other underthings in a matching color (black). Then I dress up in a long forties dress with black paisleys and bits of turquoise, a sort of black jacket with a jet-beaded collar, a pink rag around my head and a blue scarf around my neck. Next are the rhinestones. Rhinestones have to occur in sets in order to be really effective so I wear the bracelet, earrings, and necklace. (Last time I was in my favorite old clothing store, my friend Renaldo who works in there started hissing at me about, ‘Did I see that rhinestone bra?’ I could have died for it.) I put on white lace gloves and go out to buy a card for my beloved: something with roses and gold. Since that sort of thing isn’t in style anymore, the only thing I can get is Chinese, but it looks romantic and there’s no greeting to cross out. I take my beloved out to dinner and give her the card. The little story inside is about my previous lover:

Randy Raye was a sweet thing I was happy to love. Dark hair and brows in even strokes across her face. Her lips lifted back from her teeth when she laughed, uncurling a quick and sometimes nasty wit. Girl with a cigarette and leather jacket, so fifties and all mine. Slim firm legs I wanted to bite and did. When she worked at the pinball parlor, her co-worker—a blond boy named Bill—started on hormones and grew breasts. One day he asked her to call him Luann. When I saw him he seemed unsettled, more vagueness across his face.

Later she worked at the parlor. Not as a prostitute of course. She couldn’t take that on, though some of the butch girls did. After we broke up I thought of her sitting at the table at the top of the stair, saying, “And these are our models tonight,” as she introduced the women. I couldn’t go up there since we were on the outs. Twice that summer I circled the block in my waitress uniform and padded shoes after a long day at work. Wanting to see her so bad was like a groove laid into me that I had to learn to live with.

My beloved is a prostitute and thinks I should try it out. ‘Would you clean toilets for seventy bucks an hour?’ I’m not interested, but I listen to her stories which are flat, like the drama has gone somewhere else. So and so come

s in when he can’t stand it anymore because his wife won’t give him sex. He hates himself for this and won’t touch her, but masturbates while she undresses and lies around. They talk about sex roles and she says he’s kind of a feminist. Every month or so he comes to the house and I take a walk for forty-five minutes. I walk around the wide flat streets of our residential neighborhood and look at the trees. The suburban silence is irritating.

I go to the promo event with my friend Shelley. I find myself edging up to Lynette with a plastic glass of champagne. She is talking to a tall thin gay man who is dressed like an Eisenhower engineer, except the crew cut is too long and sticks up, bristly with dippity-do. Circling them inconspicuously, I hear Lynette say, “I can make love to a woman like her very best lover.” Instantly I imagine her in my grainy cotton sheets and flush, decide to head back towards Anne. I pass Lynette’s partner, Cheryl. Blond, wearing a red satin merry widow and fishnets, she’s dealing with the radio reporter, a rather anxious looking feminist. She speaks soothingly into the microphone: “…a luxury item, in the same vein as getting a massage. You pay for my undivided attention. There’s no responsibility or performance anxiety for the client to deal with, because it’s all for her. The woman’s pleasure is our only concern.”

When a stripper’s show is going well, the air is thick, charged with sexuality, and she is in total control. This pleasant feeling of immunity is close to contempt. As in the fantasy of the passive man, the stripper takes pleasure in being a tormentor. While I think all of us strippers felt some disdain for men, the only women I ever heard admit to feeling that pleasure were gay women.

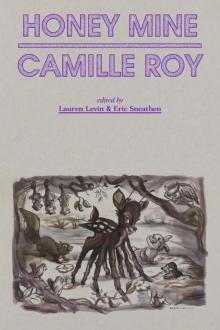

Honey Mine

Honey Mine