- Home

- Camille Roy

Honey Mine Page 5

Honey Mine Read online

Page 5

—Very good, she said, and released me.

I sprang away from them as though I’d been pushed, and when I looked back, Pussy was already extending her slender hand to someone else. You don’t know my name, I wanted to cry out.

Instead I found Shane and Willa. They were sprawled on the green velvet of a Victorian couch. It was the living room, and all the furniture had claws. Vases of tall, slender throated Calla lilies were everywhere.

—Did ya see them? Shane said. The friends of Mina Loy. They hang together like I don’t know what.

—Oh Shane, Willa sighed. He has worries that roaming packs of ancient bohemians will spoil…

—Shut up. Lemme show you.

—…the little town of Ruby Ridge, Colorado, she continued, and snickered.

Shane led me past the finger food, through the French doors and onto the patio, where three violinists were skewering their instruments. Then he stopped.

—There they are.

He pointed at a group of ancient hipsters perched on lawn chairs. They were slim and small and wore black. The man had a shaved head, paved with freckles and tiny wrinkles, and the women wore muscular silver jewelry with large dark stones. They were intent on eating. Occasionally they would stop and chew, surveying the party with total indifference.

—What’s the big deal, Shane?

He gave me a hard look.

—Faggot, he snorted, you haven’t got a clue.

Whatever. As I walked home with Shane and Willa, it struck me. An instant of clarity sparkling like morning dew: I could invite Isabelle to this tea. I ran into the house and called her. She seemed unsettled at the idea. What? Where? Why? The questions came out like slow complaints, reflective bottoms under every word—that was Isabelle. Basically solemn. Finally, with reluctance, she agreed.

Tea

Mina met us at the door and walked us into the living room, where Isabelle and I sat together on the claw-footed velvet couch. Pussy was standing next to the grand piano, her black slacks crisply pressed. She sipped something green. Absinthe? Mina was wearing an ostrichey dress, the color of old film, with tatters or feathers hanging from it. It gave her a vagueness, like Big Bird, as she stumbled across the living room floor with our tray of jasmine tea and ginger snaps.

—It’s remarkable…I can’t believe it…someone in this town knows my WORK, she said.

—You know Mina’s work, Pussy repeated softly.

What would I say about it now? I don’t like it. It’s a fish bone in my throat. It grates on my ear. With deliberate awkwardness, it occupies lyricism like an enemy territory. But that makes me return to it and savor it. It’s my crush. Back then I was too passive and suspicious to formulate an intelligent question, but there were lines I’d always wondered about:

Your drifting hands

faint as exotic snow

spread silver silence

as a fondant nun

What the fuck did she mean by fondant nun? But I didn’t ask that, instead I mumbled how much I liked the work. I had never used the term the work before, and it was followed by a risky silence, in which the ladies looked at me like disturbed cats. Isabelle’s cheeks were turning a tender red. The party was stranger than she had expected. This gave me a pang, which turned to nerve, and I splattered our gathering with another Mina Loy poem:

Your chiffon voice

tears with soft mystery

a lily loaded with a sucrose dew

of vigil carnival…

—I love that, I lied, my voice cracking.

It didn’t matter. Isabelle turned to me with a smile, all the fierce little prongs of her teeth displayed.

—I love it too, she said.

Mina settled herself on the couch next to me and ran her cool fingers across my wrist.

—You’re not from here, are you dear?

—Oh no, I said.

She gave my ear lobe a hard squeeze.

—It’s excellent for the ear. Memorize as many poems as you can. That’s my only advice.

Then Pussy stalked to the turntable and put on something very old and sexy, Louie Armstrong’s “Mack the Knife.” Mina raised her big head, with its clean, broad cheekbones and strong brows, a beautiful face even near the end of her life. She stood up, held out an arm, and they began to dance, the feathered tatters of Mina’s dress swaying against Pussy’s black pants.

We watched them. It seemed there was plenty of time. Sometimes it opens and sucks your eye down like a well. Time, I mean, and at the bottom are watery faces, like your own but cold and probably more elegant. It was like that, watching the two old women spinning across their love puddle, back and forth, in a sort of silent film loop.

They seemed to forget we were there. Finally, Pussy told us to run along.

—Go prowl, girls… Explore. Anywhere you’d like.

Mina half-opened her eyes and whispered,

—Upstairs is better.

We walked stiffly through the hall. We began to run as soon as we were out of sight. The whole house. We had it. There was a moment of excitement when something may just as well have yanked me up by the armpits and through the ceiling, plaster cracking and falling everywhere. Of course, that didn’t happen. I saw a white flash of Isabelle’s underwear and then we were at the top of the stairs, breathing hard, where four large bedrooms were laid out in a square. What were they like, Pussy’s bedrooms—people have asked me that. But people, get a clue. They were about as sexy as a 19th century bank. The bedspreads were white, with nubs like towels, stitched in a pattern of turkeys and Indians. Lace doilies sat on top of stout, heavily carved dressers. Isabelle and I walked down the hall, peering into each room. Was this all there was? The beds were four poster and sat in the middle of their territories like forts.

Then Isabelle found the door to the attic. It opened with a creak and a soft push of new smells: dust and abandoned furniture. Heat. Nervously we climbed the narrow stair. It was dim at the top. The only light bled past the rim of a window shade, pulled all the way down, but it was enough to make the white porcelain doorknobs gleam. There were twelve porcelain doorknobs on twelve small doors.

We opened each one. Each room held an iron bedstand and a dusty table.

Only one of the beds had a mattress and it was stained. The threads were worn in the dark places, as though someone had lain on it for a long time, barely moving.

Isabelle sat on the mattress and traced the outline of the stain with her finger.

—Whaddya think this is?

—It looks like a body shadow. Someone died here… Or was an invalid? Maybe an insane aunt…

—Look at my arm, she said.

I sat down next to her. I could smell the sweat under her armpits and a slight sweetness coming off her hair. Hair rinse, probably. I rubbed the spot she had pointed to gently with my thumb. It looked like it might hurt. A rash of tiny bumps had spread across her skin. She pulled at the hem of her dress where there was another red patch.

—Look, there’s another one…

—You’re getting rashes, I said.

Stating the obvious. I wanted to put off doing anything, just for a moment. It’s that feeling of being about to tremble under a coat of fresh paint. I leaned over and pressed my palms into my eyes, flooding myself with reds and oranges—eyelids are a sheet of bloody laundry. Inside, something to count on.

When I raised my head again, she said,

—You scratch it.

So, I ran my fingers around the perimeter of the red mark on her thigh. Then I dug in with my fingernail.

—What does it feel like…

—A hot spot. It happens to me. Don’t worry about it.

She was looking down at it, frowning.

—Do you want to leave?

—No.

We sat for a while next to one another, on top of that disintegrating stain. She said she liked the way it smelled up there, like dry roasted dust. She laughed and I looked at her and it seemed that her face had gone s

oft, or had just gone somewhere, leaving behind two eyes and a pouch of skin… I tried kissing it. Her breath deepened; a sigh emptied out.

I climbed on her hips, up on her white panties and I sat there for a moment, looking. It was so unfamiliar, a girl rolling between my legs and the little blast offs in my blood. She gripped the mattress with both hands, arched her back, and it hit me: I could be anyone. What a blast, what a fucking relief. Curious all of a sudden, I reached my hand down, along my back and ass, and reached for what was there. Whatever it was, under the girlish white underwear, the fine black hairs. Her impossible sour and wet surfaces.

We were up there awhile. Years, possibly. When we came down, Mina had left, and Pussy was reading the Wall Street Journal at the dinner table. The dinner dishes had been pushed aside. When she heard us she took off her reading glasses.

—Hullo, girls, she said. Welcome to the ground floor.

We stared at her stupidly.

Pussy nodded at a book on the table.

—This is Mina’s Lunar Baedeker, the 1923 edition. A treasure, really. Someday it will be valuable. It’s even autographed.

She nudged the book towards me.

—Camille, Mina wants you to have it. Now tell me, how did you come to know the work?

The question slid in like a fishhook. I understood perfectly, or thought I did. It was another variation of the question How did you ever live? How how how, and now. I picked up the book slowly. I felt its spine with my fingertips. Suddenly I was almost too tired to stand up. The truth sagged out of me.

—Pearl—that’s my mom—she covered our bathroom walls with these poems.

—I see.

Pussy knit her fingers together.

—Well, we loved having you. It’s delightful having girls prowling around, and so unusual, around here…

She cleared her throat. We watched as red points formed on the tips of her cheek bones and when she finally spoke it was the driest thing I’d ever heard. Water without water in it, a dry spring bubbling out of dry earth. She said,

—We want you to come back. Mina insists. It would give her great pleasure. Next week?

We stared at her again, but this time it was work. It’s a grind discovering anything, even when you are a spy. You have to adjust. Finally, Isabelle answered, almost sadly,

—We will.

Tuesdays

Isabelle was a dressy girl. It was like she wore herself, and then slipped some simple dress over that. Always dresses. On Tuesday evenings, they were the only spot of color in the room. I remember one which was lime green with a blue hem, sleeveless and short, that she wore with sandals. I ran into Isabelle one evening out on the street, when she was wearing the green dress. We looked at one another and the air seemed to twist up. I’d just learned to make her come but I hadn’t used that word yet.

Because I snubbed her, Willa and Shane never saw her. We all walked by, headed to some stupid bar or party. In my world no one knew her name but me, and I kept it that way. It’d be easy to twist that into something filmy and reticent, but in fact it was just her eyes on my turned back and I didn’t feel a thing.

She had those rashes. She’d sit on the edge of the mattress and we’d watch it grow outward from one tiny spot, stopping when it got to be about the size of a quarter. Sometimes it crept down her thigh like a brush stroke, and I’d follow, with my finger or tongue. It was boredom, scraping from the inside against her skin, trying to get out. She liked to kiss hard. Maybe that was the same thing—boredom. She’d pull me towards her by the throat.

Isabelle was the kind of girl who’d lay back, throw her arms over her head, and she’d be there. It was like asking someone for a quarter and they fill your hands with so much change it spills out from between your knuckles. It got to me, but it wasn’t me, if you know what I mean. That’s a load of bullshit. Usually I made the first move. Why not? Every move was a plunge. It drove me nuts. I’d spin into that world and she’d be there, inside it, waiting on the mattress in one of those dresses, with her rash spots. Somehow, she was the girl and I was the big mess. But the rashes went away as soon as she came.

Answer this question: What’s the difference between desire and slither?

Strange stuff began coming out of my mouth.

—All your pubic hairs are citizens of my country, I told her, and we both cracked up. I started calling her Pussy. Pussy this, Pussy that. She didn’t seem to respond one way or the other. Then one night with a quick jab snapped my jaw shut on my tongue.

—Ow, I yelped, blotting my tongue on my hand and looking for blood.

—What’s the matter… Cat got your tongue?

—Don’t do that, Pussy.

—Quit calling me that.

—Oh, all right… I drummed my fingers in the soft spot that stretched between her hip bones, just under her belly button. I loved it there. Happy Trails…

—You won’t believe what Shane calls me… I said, plugging for sympathy. Faggot.

—That dipshit. You don’t even look like a boy. Why does he call you that?

—I dunno.

—I can’t believe you don’t just deck him.

—It paralyzes me, or something.

—I’d deck him, she said. You’re the pussy.

—Yeah right, I sputtered. I don’t think so…

—Why not?

—Well for one thing, you have such little hands.

She held them up and we both studied them, as if they were her puppies. They were lean and strong, but very delicate. Whippet hands.

—What should I do with these? she said and thought about it a few moments. I’m gonna be a jazz musician.

—But you play the violin.

—My dad is a jazz musician.

Then she named someone famous. A trumpeter, Italian, sort of Hollywood—Dion with swing. One of his tunes had infected the radio waves for at least six months. I’d heard it a lot, simply because I was among the living. So, what if it sounded like shiny ripples beamed at the masses from a celebrity golf tournament?

—Wow, I said, impressed.

Isabelle looked at me with scorn.

—It’s not what you think. I grew up in Santa Monica.

I buried my head in my hands. Clueless again, what the fuck was Santa Monica? I mumbled that question and it seemed to loosen her sympathy, finally. She took my hand and nibbled on my fingertips. Between nibbles she explained,

—It’s a California beach town. There are hippies everywhere, even on our lawn. Actually, I’m not allowed to talk to them. I run from the door to the curb, and practice violin. That’s my life. Christ, my dad is such a control freak. Last winter for two months we had only nuts and fruits in the house. That was his detox diet. But he’s still a pothead. Our house stinks.

She put my hand down and stared at me glumly.

—I’m going home soon. What a crashing bore.

The day Isabelle left I came back to the Budd house and there were five Birds of Paradise in a vase on the kitchen table, and a note which read,

For a bird of paradise xxx Isabelle.

I was so stunned I thought a quick shit was going to run out of me. When I staggered to a chair Marian came to me and gently put her arm around my shoulders.

—We can’t always control the kinds of attention we get, dear. It’s not your fault.

Then she took the flowers, broke their stems, and stuffed them headfirst into the trash.

Secret

When the next Tuesday rolled around and I was reading a comic book, my body got it: she was gone. On Wednesday, also, she was gone. Then she became one of the miscellaneous cravings to which I seem to be susceptible. It could happen anywhere. I’d be chugging a beer next to the pool table in the cowboy bar and by the time I put the bottle down I was in the middle of an Isabelle flash. Then I’d peer out at the bleary crowd of beards and flannel shirts from inside my little room, the one in my brain.

I felt sort of special. My secret was my message, and it came

back at me in the haywire sunshine sparkling on the crystals under my boots, reflecting off bits of ground-up mica in the dirt. I found a chunk of watery blue turquoise on a trail and gave it to Willa. It was poor quality but pretty, and I felt generous.

Willa and I did the rodeo. During my event, the barrel race, my horse fell over and crunched my foot. He was pigeon toed, unfortunately. Afterward I discovered I liked limping around. It made me feel bigger and bloodier. Wounded. Shane had gotten thrown from a bull, dislocating his shoulder, so Willa was the only one who brought home a shiny plastic trophy (in Pole Bending), three inches of gold cup on top of a podium of imitation wood.

The trophy was sitting on the kitchen table the morning Shane opened the newspaper to a shot of serial killer Ted Bundy, taken at a press conference after he had been captured by the Ruby Ridge police. He wore a big happy-to-be-in-your-town smile, so that the handcuffs seemed incidental. We passed the paper around. His face was a bundle of even features, high cheekbones and brown hair, so generically handsome he resembled no one in particular. The cops were grinning too. It looked like a party celebrating law enforcement: from concept to action. The press peppered him with questions. Who are you? Why do you kill for thrills? Instead of answering, Bundy went around the room and gave each journalist a satanic fortune cookie. That’s how it seemed. Actually, he just answered the questions.

—Each of us is as unique as a snowflake might be. But that’s not to say that I’m so special that no one can understand me, or nobody has the capacity to understand me… I’m not unique… although obviously special.

The richest part, what really killed us, was that only hours later, before press-time of that same day, Bundy escaped. Apparently, he’d wriggled out of his cell through the air conditioner tubes.

The presence of a serial killer frog-kicking through City Hall’s ventilation system somehow made Willa want to go swimming. She offered to buy the beer. The parties wounded in the rodeo, Shane and I, could sit on the bank and drink while she jumped in and out of the river. I liked the spot: sun on the wildflowers, the river bouncing over massive brown boulders and tossing cold spray. A moldy abandoned cabin at the site had been the location of an infamous party, which Willa and Shane had described to me in loving detail. A friend of Willa’s had found a sack of cocaine while he was hiking right outside of town, and he’d thrown a party for everyone he knew. I was mystified.

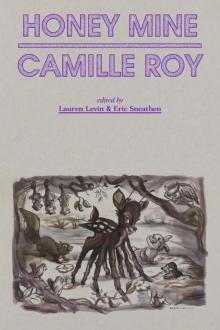

Honey Mine

Honey Mine