- Home

- Camille Roy

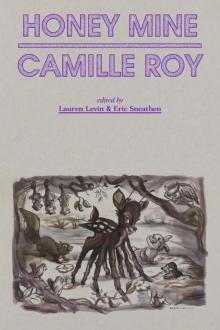

Honey Mine Page 7

Honey Mine Read online

Page 7

—Fine. Come on.

I gave Amy a leg up, then a hipbone, then a shoulder. I had to push her up by the soles of her feet. With a mournful yelp she hit the ground on the other side.

I went up in one deep breath, scraping my knuckles, then grasping for the rusting spikes at the top. They looked like medieval spears, as though a line of soldiers had been bricked into the wall. Once up, balanced perilously on my knees, I paused. The moon faces of my companions were turned towards me, my nearsightedness rendering them expressionless. Two creamy white blanks. What shocked me was that there was no lawn. What did I expect—croquet? Amy and Carol were waist deep in what looked like a cloud of dust. It was weeds. There were a few random, forlorn trees on the lot, which took up most of the block, and then the black rim of the surrounding wall.

I didn’t feel nervous anymore. I’d blasted into one of those time-stopped nuggets, giddy and criminal, yet loaded with the luxury of the pause.

I crumpled to the hard ground. When I stood up, Amy’s fearful eyes were locked on me.

—Everything’s fine, I told her, in a normal voice.

I felt so relaxed, I thought I could give relaxation to anyone.

—How am I going to get out of here? Amy whispered hoarsely.

—We’ll call the fire department.

—No, Carol said. We’ll tell the butler to call the fire department.

The laugh loosened us up. The nerve Carol and I shared was wiggling with pleasure, thrilled to be here. The two of us struck out alongside of the house, as Amy scuffled behind, whimpering whenever she stumbled over a rock.

—Guys, can we take out our flashlights yet?

—Alright, alright.

I stopped and pulled them out of the backpack. Three weak beams played upon the wall. Graffiti that vanished with a stroke. Then we started strobing Amy with the lights. Her t-shirt slid up and her belly button caught the beam.

—Hey guys, don’t, don’t, please, you guys!

Carol’s laugh wobbled into a shriek.

We continued plodding around the house, looking for a way up or in. Finally, around the other side, we found it. The way in. It was terrifically wrong.

—Freaky, Amy squealed.

It was the payoff moment. Amy made little steps and twisted her hips as if she had to pee.

A huge bite had been taken out of the Isher House wall. Cautiously our flashlights traced the ragged outlines of the hole. One brick after another slid under our beams, stubby and broken and dusted with gray powder, as if the connective cement was dissolving. Our flashlight beams wavered over the central darkness. Then Carol was up at it, her hands grasping the lower edge.

I scrambled up there, joining Carol astride the crumbling wall. I remember her breathing next to me, that steady sound.

—Wow…wow, she said.

A staircase was attached to the cement wall of the basement, but the stairs only went halfway down. The last step was askew, and the rest had fallen away. Our flashlights followed the deep cracks that marked the missing steps down into the basement. Down there, at the heart of it, the wainscoting and floors had collapsed into a mess of decaying beams. Here and there were the black gleams from stagnant pools of water. Greenish shards looked like they might be pieces of roof. There were drifts of white stuff which was probably decaying dog shit, but it didn’t smell. Isher House didn’t look like anything, except scoured. The deepest vacancy, the ruination of the familiar.

—I can’t believe they even kept a dog here. Stupid for us to go down there, Carol said, gesturing dismissively towards the basement.

I nodded, too disappointed to speak. It felt weirdly like being abandoned by the past.

Within a few months, the house was demolished as a hazard. The surrounding wall came down too, which meant that everyone I knew swarmed the weedy grounds and inspected the scrapings of rubble which were all that was left of the famous House. I went again, but this time I was by myself. Carol had stopped returning my calls.

I knew I’d been dumped when I walked into our ninth grade class and Carol had moved from the chair next to mine to a seat on the edge of a cluster across the room. She moved, in other words, from me to an empty spot next to the Black girls, who looked at her doubtfully. She was wearing a sideways-draped baseball cap. It went with a new attitude and slang: talking “Black,” which for Carol meant barely moving her lips, while slurring her words ironically. It was beyond embarrassing. That first day a thud of astonishment went through my classmates, but after a week everyone seemed to accept it. It was weirdly amusing, this version of Carol, even to me.

It was also excruciating. She quit saying “Hello” to me, and started saying “Yo” to everyone else.

Carol didn’t make new friends. She’d dumped me for a zone with no one in it. There wasn’t a word for where she was, or an idea that related. It was against the way things worked, which was quite specific: kids played with anyone. But teens travelled in racially separate packets. If you’d asked us, I’m sure everyone would have said the same thing: we’re just more comfortable this way. But what does comfort mean, when everything is uncomfortable? It was the history we were stuck in, and there’s no boundary. It just seeps in.

I sat in class and watched our teacher, Miss Adele, stunned. She had been the teacher we had loved together, on the basis of her warm good looks. Miss Adele was a little woman, with tiny hands, but big cushiony breasts and springy hips.

—Like a baby with equipment, Carol had once whispered.

Before Miss Adele, we hadn’t believed an adult could be adorable. Then we heard the sensational report that she had been held up at gunpoint, but refused to give the robber any money, and her reward was to live in the fuzzball of our incredulous love. She had kids too. What a badass. We wrote her fan notes during class, which we stuffed in our pockets and burned up later with matches. More little secrets. Now Carol wouldn’t look at me. What was it all about?

I glided into a funk that lasted until the following year. In the middle of it, Carol was yanked from our class into something special—an academy downtown for students so gifted they needed to be rescued from failing schools. I didn’t have time to be jealous, she just disappeared.

I hear news, once in awhile, even after twenty years. I ran into someone who reported that Carol’s head was shaved, barely fuzzy, and purplish red. How does that work, having no hair and dyed hair, on the same scalp?

—Did you know Carol was a doctor? my informant asked.

No, I didn’t know that.

—Remember Helen Chute? She’s living with her. As in, they’re dykes. Helen Chute, who used to run DePaul Hospital. And they’ve adopted three little boys from South America. There’s Pablo from Peru, Henry from Columbia, and another one from Brazil.

But Helen Chute must be pushing seventy!

—The paper ran an article about them.

I admit, it bugged me. News of divorces, mental illness, addictions, the legal problems—it’s easier to take. When I heard about Helen Chute and Carol’s boys and Carol’s lesbian hair, I experienced a deeper pang. Perhaps I sensed yet another thing I should have done—become a lesbian? What an embarrassing thought.

She had a new lesbian name too, flowery but assertive. An appalling name, actually, one that stuck out like a little sign which said, I am not my father’s daughter. Which is what she said, I heard, to someone from our school.

But you are your father’s daughter. That’s the truth.

And I’m here, pacing the floor, in my little truth shack. Welcome, Carol. It’s cramped, and it annoys me, but it’s what I have. It rents by the month, sort of. I didn’t know this was going to turn into a letter, but writing has its own logic and I need to let myself follow that (according to my drug counselor).

DEAR CAROL…

It’s been a long time. Hope you are well, et cetera. It’s winter and I’m holed up in the small coastal town of Two Creeks, Oregon. I came here for fog, cold beaches, and wholesome companions. Have yo

u ever needed to chill out? I have tried it before, and to tell the truth, the boredom became so stifling I was willing to crawl out through the air conditioning ducts. This time I’m trying something different: every sick thought gets flushed to the page. The writing cure.

Do you remember the intersection of 47th and Jennet? Crossing from north to south would get your ass kicked if you were white and vice-versa if you were Black. Fuck was life, at least in our part of Chicago.

So I left. And I discovered a fucking big country. You must have noticed how dumb this country is. I’m still not used to how many white people there are. How did you deal with the stress of hauling your ass across the map? How did you arrive in the visible world?

A year or so ago I ran into Amy Brooks. She’s thin now and has wrinkly eyes. She couldn’t remember the night we tried to break into the Isher House. I asked what she did remember from the old neighborhood, and she admitted she had no memories at all. Just an emotion: fear.

I remember everything. It’s a distraction, like being haunted.

But I liked the streets after a rain. All the airborne soot drained down the gutters and the cobblestones were shiny.

It’s been two weeks so I’m allowed day passes to get out of the house. Today I walked down the main street of this little town. It was lined with ornamental fruit trees and the branches were dripping—black shiny branches, no buds yet. They looked like the writing on this page, all jumbled up. The street took me right down to the ocean and then stopped in a cluster of concrete cubes. I sat on one and felt the wind-blown sand scratch my face, erasing it. I don’t know what I want. Whatever comes after this blot of time they call rehab, the thought of a new lover or job, it just exhausts me. Is there something else, an empty space, that I can go into and touch? With my instrument: a liquid spade, and my heart: a fear radiator.

Do write back.

Sincerely,

Camille

X and I travel south through a county

of big white cars

& sweet plums—

there’s funk on the radio.

I wear a low brimmed hat with a feather.

X has on stockings and heels, there’s a jaunty cut to her coat.

She says With you I felt no guilt.

I was willing to do almost anything for that.

Her cigarette makes a red spot in the dark.

I look out at the lights of Bakersfield, Rosedale, Oildale.

The industrial rim marks a boundary

between the city and the desert. I’m shy about death.

Before the factories shut down I could see fires

from my window at night.

Car wheels churn gravel up a steep driveway. Ocean, clouds.

I meet Alfred. The ex-husband has a moist tan.

He gives me a room alone

a sky blue window ledge

comfort at being enclosed.

In the afternoon X

presents herself,

looking smart

in a black dress

and little red hat.

I’ve put on my grey silk tie.

We’re compatible in a way,

says X. I like you, and you

like my looks.

I have a slip.

White rags

spread with a butter spoon

soft spotting under

my skin—

it’s so easy, at first—

my tongue laps her cheekbones

thin as rails

something I lean against while looking out

on a ship,

a tanker,

spidered with helicopters.

Distant line of fire.

Later, we watch one another

as indifferent Alfred smooths the sheets.

When I was small the world started at my stomach and melted outward in waves. My sisters ate at the same table. The three boys were farther and measured in their distance, moving like a clump at sunset along a cord stretched between two women. One snipped the flowing butt off a firefly and put it on my finger.

That was Sam. When I was fourteen he did a slide show, a week after he got his discharge. Pictures of dead people taken by someone I was related to was the closest I’d ever been to death. The bodies were lying in tall grass and were hard to see. Sam had smooth eyebrows over brown eyes and a sloppy jaw, jerky with amphetamines. He’d enlisted because he loved Goldwater and when he got out he was a drug addict. But at least he learned a trade.

Sam was the cousin who leaned down into the window of the sandwich shop, grinning. He’d landed the helicopter in my parents’ front yard and hitched into town to see me. Around that time there were rumors he would fly for anyone—running guns or drugs for the wrong side in small countries. It’s not impossible. Sam worked whenever he wanted, otherwise lived in a trailer with a woman named Sara.

Composition is like a new car, or kitchenettes.

It creates a frame around disconnected events.

So after Sara left him for nobody, leaving no note,

Sam wrote a spy novel. That’s the story.

For X, sex is a combo of string and

past tense. It covers her yards of mouth.

I lick the flesh like an envelope. (Bondage.) Says X,

How bad were you today

baby. Her knees press my temples,

there’s a curly fence near my mouth.

(Imploded recognition.) When I learned

about gender I was very surprised.

The proceedings slid from a folder,

there were loose papers all over the floor.

Before that, I had only

experienced animals. It’s not impossible,

I thought,

Anyone who likes to be fucked is a

girl,

anyone who only likes to be fucked is a

woman.

The soft light over the Los Angeles hills seemed rubbed with an eraser. I was 16. I felt like I was hitchhiking, since I hardly knew the cousin who was driving. His name was Jim.

His pickup had beer in the back. We drove up a canyon to his place, an apartment in a weathered turquoise building next to a stand of eucalyptus. It was June, and the eucalyptus

had dropped dry skinny leaves all over the parking lot. We walked up the stairs; inside were Sam, Mike, my sisters. Jim’s apartment was a one-bedroom with a kitchenette.

Mike pulled open the back door to show me what a fucked place it was: the back stairs had been torn down so the door opened on empty space. Mike was the family golden boy,

he turned in the light like a fish, sluggish. He left the door open and settled back on the couch, next to Sam, who drew his long legs up. It was twilight and through the open door

the sky was turning a deep blue streaked with smoke. There was an odor of beer. Then the cousins made a show of picking up and flipping through some porn magazines.

My sisters went for it, arguing like their own sincerity was forever. It was hard to take. My grandmother was new in the dirt, buried that day and no one could shut up (except me).

My sister said I shouldn’t have sex until my nipples turned brown, which I figured she thought would never happen. She was older, and kept her drugs and screwing

in the basement the same way she kept her jewelry there. Her lovers were thin white men whose trouble was drug-related. When Paul left Cook County Jail he carried an odor of rape

he had large nerve spots in his eyes. Fear moving like a breeze in a prison yard, I could feel that in my stomach when he was around; otherwise I didn’t care. I thought about Monica.

Her sharp teeth and brown cheeks. The way her greed slid across my hips could be scary but her palms were narrow as slots, that made it okay to have sex with her.

Monica was Black in a segregated city; so the closer we got

the more transparent I became, my longing vicious

as wavering lights of association. Relation—the spot wher

e

we’re the same, or at least rolling downhill on a boulevard

lined with palm trees and novelty shops.

So when Sam said, Any real man would rape a 14-year-old

if he saw her naked,

it shut me up.

Pressure doesn’t yield a true statement but softens

underfoot,

like nylons in a wad. It’s more than gymnastics.

Doors and windows of the body squeak, light as paper.

This carpet I’m eyeing glints back

an acrylic mat, fishy browns.

Next on my list

Thrusting

my hand through

the ribs of X

Warm slimy blood

on my fingers,

bits of bone

What a mess.

I want to do

something

for you,

I say

to X, staring

at my hand.

I wrap it

in my shirttail;

now it looks like a bandage

thought the gesture

was sexy & fun.

One day after school Monica brought me home.

I sat on a yellow chair and we listened to the radio: WVON, Otis Spann The Blues Man, coming from the kitchen. A plaid couch was covered with sisters with white teeth and dark skin, laughing at me I thought. The rooms were hot, or just full of the weather and leaning out over the window sills I saw white stone pots of geraniums at the door. We watched the street—a tall drunk wobbled after a woman in a flowered house dress whose crooked eyes bulged out in two directions. She turned and hacked out a laugh. Monica said her stomach split every year with a new kid.

Or was that my block?

I liked the closed-in feeling—relation defined through position and abandonment, the meaning of fix. So the streets were deserted after dark and any stranger carried death!

It’s one a.m., and the snow is falling through a web of fine black particles, soot from the mills. Monica’s shielding her cigarette from the wind while I try to remember where I am; on a block that slides uneasily from white to Black. She’s wearing a red T-shirt under the black jacket. We’ve just come out of the basement. We started out watching each other, lips back, drinking beer. Where our skin slides together along the damp basement wall, there’s a streak of feeling like a welt. I open another beer, to sink this awful strangeness. Then her palms are warm and under my jaw, sliding back around my head. That’s okay, so I peel off her t-shirt. it is very interesting how dark her nipples are. I touch them with my fingers then my lips then I lean back, feeling thin as a sheet. I’m washed out, ripped. She kisses me clear to the back of the throat, where the tongue splits. I figure I don’t

Honey Mine

Honey Mine